Last year I worked on my own transcription of Albeniz’s Asturias as a research project for my studies. The first obvious place to look was the piano original, then I looked at transcriptions from Fortea (sometime before 1920), Prat (1920), Segovia (Published 1956 but he was playing some version of Asturias as early as 1924) and Yates (1999). Listening to the original it was obvious that a note for note rendering of the original wouldn’t be possible on the guitar for a number of reasons, among them an unsuitable key, impossible chord voicings and a wider range than the guitar allows. For this reason many choices must be made by the transcriber and/or performer to make the piece work. It was fascinating looking at the approaches these four transcribers took in solving common problems, as well as what liberties they took beyond simply trying to remain faithful to original. By the way I’m referring to the piece as “Asturias” because that’s the name it’s most often known by – even though this title was probably given to the piece well after Albeniz’s death, and the piece clearly references Andalucia rather than Asurias in Spain’s North. (Stanley Yates gives a great explaination of the back story of this here).

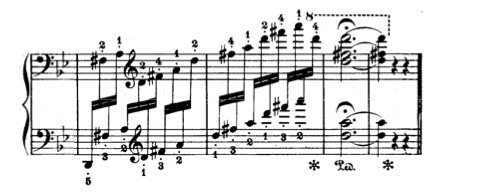

Let’s look at the opening allegro section. The twelve beat melodic cycle and accent every 6 or 12 quaver beats is reminiscent of a buleria. The constant peddle-point sitting in the middle of the range of the melody imitates the popular guitar device where an open treble string is used to play a peddle point with the right hand index or middle finger, while the thumb plays the melody using the bass strings.

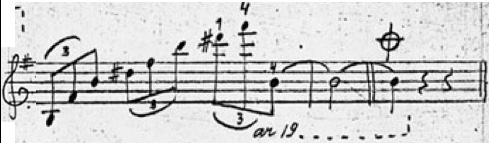

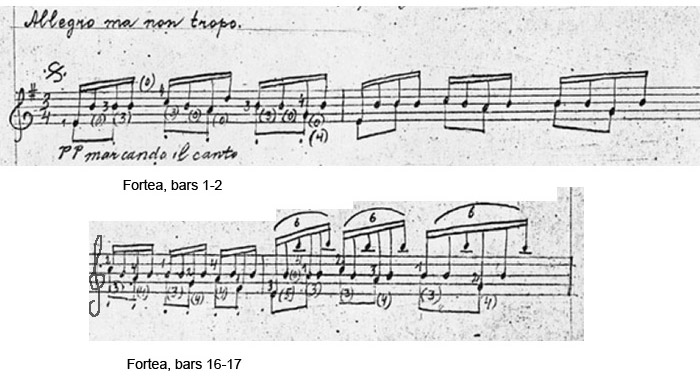

This is clearly a piano pretending to be a guitar – so what happens when we have a guitar pretending to be a piano pretending to be a guitar? let’s look at the same bars in the earliest transcription I know of, that of Daniel Fortea (a copy of which is available from Matanya Orphee’s website here):

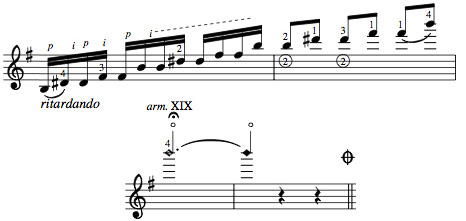

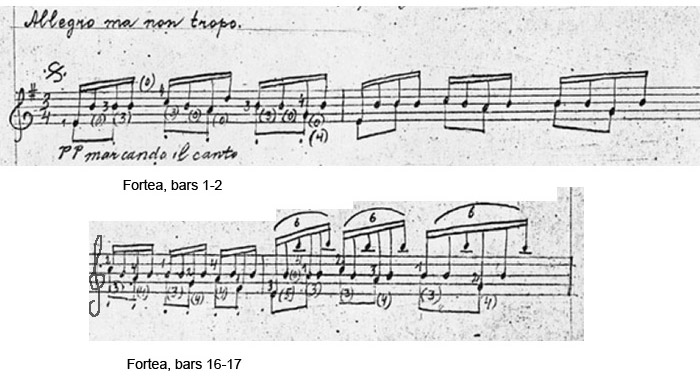

Fortea keeps the staccato marks of the original, as well as the dynamics and other indications, intact. The Interesting thing is that he adds a triplet figure not in the original. This figure continues on for most of the first section, and has been copied in most subsequent transcriptions; Prat and Segovia do pretty much the same thing, minus the staccato marks. Of the four transcriptions I looked at, only Yates looked back to the piano original:

The triplet figure has been attributed to Segovia before, however it does seem that the idea was already in common use before Segovia made his transcription – Segovia mentions in his memoirs that Fortea’s transcription had been the one he’d seen played up to the point he started working on his own transcription.

So why add a triplet figure? While we can probably never know the reason for the addition of the triplets, they make sense in light of certain compromises which must be taken as the piece is carried over from the piano score. In the original the dynamics move gradually from pp to fff over the first 32 bars. The guitar has less dynamic range so cannot reproduce this crescendo to the extent Albeniz would have intended. Also the crescendo is heightened in bars 25-32 with the accented chords appearing every 3 or 6 beats, which become more and more widely spaced, culminating in bar 33 with a G minor chord stretched over 5 octaves. This is not possible with the guitar’s range. To make up for this, the triplet figure adds weight to the sound giving more of a sense of crescendo.

The other interesting thing is the stacatto marks, which are kept in Fortea and Yates but eliminated in Prat and Segovia. The staccato markings I believe are part of the attempt to make the piano sound like a guitar, more specifically a flamenco guitar. The flamenco guitar is built traditionally to have a strong attack but not much sustain. The classical guitar has more sustain but still much less than the modern piano. For this reason I feel keeping the staccato marks on the guitar version may be misguided – if it is a device to make the piano sound like a guitar, there is no need if one is actually playing the guitar.